Despite their uniqueness, Donetsk and Lviv regions share certain features related to the development of the coal industry in both regions. In the 1950s in the Soviet Union coal was considered to be a major energy resource. In order to increase its production new mines were built in Donbass, and in Lviv-Volhynia basin. Construction of coal mines led to the emergence of new cities and towns in Eastern and Western Ukraine. Certainly, in Donbas this process was more extensive.

As a result, multiple small and medium-sized mono(one-industry)- towns sprang in Eastern and Western Ukraine. They were centered around mines: coal industry employed more than half of their population. More than 40 such settlements were built in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Among them – Girnyk, Dobropillia , Myrnograd, Novogrodivka. In Lviv towns of Chervonograd, Sosnivka, Sokal, Girnyk and others belonged had the same origin.

Many of these towns, such as Ukrainsk, Girnyk in Donetsk region or Sosnivka in Lviv region, were founded “in the middle of nowhere”, near the coal fields. Initially, mine-builders settled around a mine that was started; subsequently, they were joined by miners and their families. When a settlement counted 12 thousand residents, it was given a city status.

The history of Chervonohrad is somewhat different. It became a part of the Ukrainian SSR as a result of the border adjustment treaty of 1951 between the People’s Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union and changed its name from Krystynopil. Deposits of coal were discovered in the town’s vicinity and soon first mines were built. The city consisted of two parts: the old part (a ‘pre-Soviet’ one, so to speak) and the new part. Even the name of the area was ‘New Town’.

The most intensively mining cities were expanding in 1950-60s. Due to labor migration population of the vast majority of mining towns increased significantly. In addition, an important source of population growth both in the West and the East was migration from surrounding villages. Many new workers arrived to Donbass coal mines from western regions of the Ukrainian SSR. For example, Komsomol construction team from Zakarpattia came to the city of Donetsk region Snizhne (the mine was consequently called ‘Zakarpatska- Komsomolska’). At the same time, in 1950s miners from Donbass were coming to build mines in Chervonohrad. In the Soviet media of those times, the Lviv-Volhynia basin was often called ‘the younger brother of Donbass’. Most of the mines constructed there were built with the participation of miners and engineers from Donbas.

Life of population of these cities was closely associated with mines: the majority of residents worked there, municipal social services were financed by coal enterprises. Mines turned into a kind of ‘provider’, on whom the welfare of miners and their families depended on. However, this dependence proved fatal.

In the early 1990s, coal industry found itself in crisis. Mines were closed down and this caused a number of social problems, both in the West and in the East of Ukraine. The decline in production, increased unemployment, significant decline of living standards, working population outflow to other regions (and often, abroad) started to threaten the existence of small and medium-sized cities.

Therefore, living conditions of miners in the mining cities of Donetsk and Lviv-Volhynia coal basins can be considered identical – the same social, economic, environmental and other problems are faced by local communities.

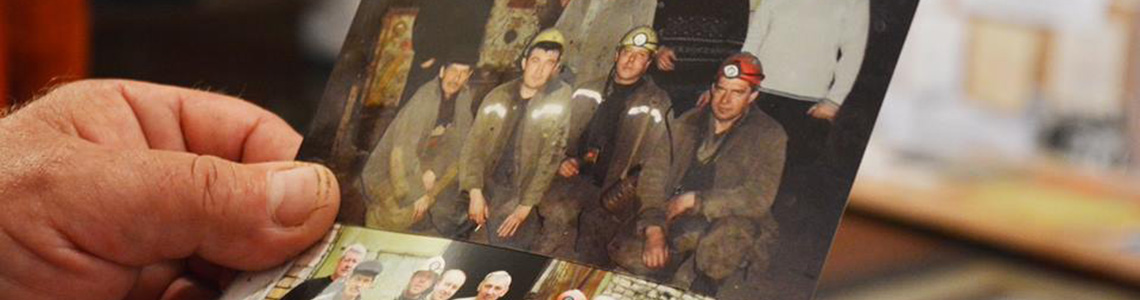

Nevertheless, it is interesting to compare lifestyles and traditions of workers from the same sphere living in different regions of Ukraine. To this purpose, an oral history project ‘Miners stories from Eastern and Western Ukraine’ was initiated. In the summer of 2016 a group of volunteers from Donetsk and Lviv regions collected life stories of 28 miners from 13 different cities and towns of Ukraine. Respondents were asked questions concerning their profession choice, family and professional events, values, future prospects of mining towns. Based on the analysis of their stories the following conclusions were made:

The choice profession of a miner was foreseeable, perceived as reasonable; it was never a subject to doubt. Firstly, there was very little if any alternative to the profession of a miner in mining cities. Secondly, a sense of team and certain traditions were also important; i.e., my grandfather used to work there, and my father, my brother, and in general, all male residents of my city. The majority of respondents were from mining dynasties, and some passed their profession to children and grandchildren. Thirdly, in the Soviet time, career opportunities and prestige stimulated choosing a mining profession. The last but not the least, high wages, higher than other’s workers, also influenced career choice.

The nature of underground work poses the mortal danger, so all depend on one another, enhances solidarity, mutual support, personal initiative, courage, and discipline. This was stressed by all interviewed miners, irrespective of where they lived.

Work in mines, in life-threatening conditions is not perceived as heroic. For miners, it is a part of their traditional collective history. The majority of respondents, regardless of the region do not remember (or remember in general) their first descent underground. For them, it is a familiar, everyday thing.

Middle-aged and older respondents regardless of the region of Ukraine noted the high prestige of miners profession in Soviet times. Indeed, it was during this period a ‘cult’ of miners’ work was formed; it was described as a ‘front-line’, difficult and risky, absolutely essential. This served as an important point of professional dignity and identity. Soviet media and propaganda helped to create an image of a miner as a strong and courageous man. Films, books and art were created to celebrate miners work. That is why it came as no surprise that miners of this age group, both in Eastern and Western Ukraine, when listing mining songs most often named two – ‘Spyat kurhany temnuye /Dark mounds sleep…’ and ‘The song of the young pony putter’. Representatives of the younger generation are unaware of these songs, at least they did not name them.

The dramatic decline of mining profession prestige took place in the early 1990s. It was related to the crisis, which started in the coal industry. The financial position of miners and their families deteriorated significantly. In the West and in the East social tensions escalated and led to a wave of strikes. Strikers’ demands were the same and concerned improvement of the financial situation.

Miners from Western region often visited Donbas. In Soviet times were coming to Donbas mines ‘to learn’ directly on the site. In addition, in Donetsk and Makeyevka they were going through in-service teaching in order to improve their professional qualifications. Thus miners of Lviv-Volhynia basin are aware of working conditions in the east, calling Donbass mines much more dangerous than their own. Miners from eastern Ukraine know less about mines in Lviv region, notwithstanding the fact that in the 1950s-60s mine-builders and miners from Donbas were working on the construction of mines in the west and some stayed there.

Among the most important values respondents in the west and in the east named family. Concern about family and its welfare is an incentive for men to justify the risk which they face on a daily basis when going underground.

Holidays and leisure are an important part of everyday life of the miners. Describing the celebration of Miner’s Day, the vast majority of miners and their families called it ‘holy’, stressing its importance. Traditions of this celebration in the west and in the east are virtually identical. The celebration is divided into two parts: official and private. During the first part of the celebrations miners are decorated for certain industrial achievements. This is the occasion for miners (though not everyone) to wear miner’s uniform with awards. In the mining towns of Lviv and Donetsk regions, Miner’s Day is associated with folk festivities, concerts and fireworks. Typically, miners celebrate with family or with colleagues who usually are also friends.

Other holidays observed by miners families in western Ukraine are religious holidays – Trinity, Easter. It should be noted that they particularly honor St. Varvara’s day (17 December), who is considered to be a patron saint of miners; this day is called a ‘second Miner’s Day’.

Miners in eastern Ukraine among family celebrations listed birthdays of their family members; they also remember Soviet holidays, such as May Day demonstrations or November demonstrations to celebrate the October Revolution.

Both in western and eastern Ukraine there are certain traditions of celebrating private events in small mining groups (teams? brigades) that have different names, such as ‘bottle’ (butyliok) or ‘goose’ (husak).

Particular attention should be paid to myth-making in mining communities. In East Ukraine miners often mentioned underground spirit Shubin, who has become a symbol of the mining profession. It figures in many legends, especially about how good Shubin warned about forthcoming accident or danger. These myths are popular all over Donbas, where the legend originated. Respondents in western Ukraine rarely mentioned mythical creatures; however, they too were speaking about unusual accidents.

Miners in Donetsk and Lviv region realize that fate of their cities and settlements depends on mines. They express the same concerns that with the closure of mines they will lose their jobs. Both miners from East and West believe that using Ukraine’s own fuel and state support for the coal industry are the best options.

Undoubtedly, each miner’s story is unique and original, but together they form a common space describing similar destinies, thoughts, wishes and aspirations, no matter where miners live. A diversity of their stories simply enriches their commonalities.

The author of the article: Ksenia Kusina, PhD., assistant professor of the history of Slavs in Vasyl’ Stus Donetsk National University (Vinnitsa), academic editor of the project ‘Miners stories from Eastern and Western Ukraine’

This research is a part of the documentary project ‘Miners stories from Eastern and Western Ukraine’, which was implemented in 2016 by NGO ‘Foundation for Freedom’ and the NGO ‘Our Future’ in partnership with the Independent Trade Union of Coal Miners of Ukraine under the support of the Embassy of Switzerland in Ukraine and Irene Prestwich Trust (UK). The full texts of mining stories can be found on the project website.

Available materials can be used for research and publication with referring to the source.